Least Tern

Scientific Name: Sterna antillarum

Description: At just nine inches in length, least terns are the smallest members of the gull and tern family. Least terns are mainly gray and white, they have a gray back, a forked gray tail and a white underside and narrow, pointed gray wings. They have a black cap, short white eye stripe, yellow bill with a black tip.

Preferred Habitat: In North Dakota, least terns are found exclusively on the Missouri River system. Suitable nesting habitat is sparsely vegetated with sand or gravel substrate and located near an adequate food supply.

Diet: The primary food source of least terns is small fish. Least terns catch fish by hovering and peering downward, when a fish is spotted they dive dramatically to catch the fish in their beaks.

Life History: In North Dakota, least terns breed from May to August. They lay two to three spotted, buff colored eggs in their nest. Their nest is a shallow scrape in the sand. The shallow nest combined with the sand-like coloring of the eggs makes them very hard to see in the sand. The eggs are incubated from 20 to 22 days before they hatch. The chicks are fed small minnow-like fish until they are able to fly around 20 days old. Because of the difficulty of diving for fish, newly fledged chicks are unable to feed themselves sufficiently and are fed for several more weeks. In North Dakota, least terns form loose colonies of 3 to 30 pairs. The terns leave the area in August and migrate to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean for winter. Least terns typically live one to five years.

Reason for Decline: Least terns have declined in number due to the construction of dams on the Missouri River. The dams alter the natural hydrologic patterns and cause unnatural water fluctuations that can cause nests be washed away. The dams also reduce tern habitat. Flooding prevents the scouring of islands and shores, allowing vegetation to grow, making the area unsuitable for least terns. Damming has also created lakes that cover natural river corridors that once contained sandbar habitat required by least terns. Although not as prevalent in North Dakota, in some areas development along the rivers has also contributed to declines in least tern numbers. Another contributing factor is disturbance from human activities such as foot traffic, unleashed pets and off-road vehicles, these disturbances can cause temporary nest abandonment which exposes the eggs and chicks to predation and changes in internal temperature.

Piping Plovers

Scientific Name: Charadrius melodus

Description: Piping plovers are small shore birds measuring about 6 ½- 7” long. Their backs, wings and the tops of their head are sand colored and they have with a white underside, yellow orange legs and distinctive black band across their chest and forehead. In juvenile birds, the black bands are not as dark.

Preferred Habitat: Piping plovers are found on the Missouri River system and on alkali lakes in the northwest and central region of the state. Over one third of the interior population of piping plovers breeds in North Dakota. Piping plovers utilize barren sand and gravel shorelines of both lakes and rivers. They nest in sparsely vegetated areas that are slightly raised in elevation.

Diet: Piping plovers feed on a variety of small invertebrates including worms, fly larvae, beetles and small crustaceans. They forage for food on open beaches, usually by sight, moving across the beach in short bursts, stops and then pecking at their prey.

Life History: Prior to breeding, piping plovers form pairs and find and defend a territory. The pair will then scrape out a small depression in the sand. Around late april in North Dakota the plovers lay four sand colored eggs in their nest which they incubate for a about 27 days. After hatching, the chicks are able to feed within hours and the adults' role is to protect them from weather and other dangers. One of the more dramatic plover behaviors is a broken wing display, in this display the plover feigns a broken wing when a intruder is near in order to distract the potential predator from their eggs or chicks. The chicks are fledged around 30 days. In August, the year's fledgling and adults migrate to the Gulf of Mexico.

Reason for Decline: On the Missouri River, piping plovers face the same threats as the least terns (see above) because they share very similar habitats.

On alkali lakes in North Dakota, nest predator increases in recent decades threaten the plovers. Plovers on alkali lakes are also susceptible to cattle trampling, wetland drainage and pesticides. In their winter habitat along the Gulf of Mexico, their habitat is being lost to development and shoreline stabilization

Pallid Sturgeon

Scientific name: Scaphirhyncus albus

Description: This odd looking fish is a relic from the dinosaur era, pallid sturgeon have been around for over 200 million years. Pallid Sturgeon are large weighing 80 pounds and reaching lengths of 60 inches long, they also live a long life, up to 60 years. Sturgeon are armored with rows of bony plates running the length of the fish, their snout is flattened and shovel shaped and they have a long thin tail.

Preferred Habitat: Pallid sturgeon are found exclusively in the Missouri River system in North Dakota. They are adapted to large shallow rivers with gravel, sandbars, turbid water, and seasonal pulses similar to large free flowing rivers.

Life History: There is little evidence of natural reproduction in pallid sturgeon in the last fifty years. It is believed that this lack of reproductive success is due to both a lack of spring river pulses that cue spawning and the existences of dams that cut off access to spawning grounds. Pallid sturgeon populations are currently augmented by artificial propagation. Development includes a planktonic larval stage. After the larval stage growth is rapid during the first four years then slows. Pallid sturgeon do not reach sexual maturity until 7 to 20 years of age. Once reaching maturity, individuals may require several years between spawnings.

Diet: Pallid sturgeon feed on insects, crustaceans and small fish.

Reason for Decline: Populations have undergone severe decline due to damming of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. Dams block migration, fragment the population and alter flow rates and temperature regimes required by the species. Different flow rates such as seasonal pulses are believed to have spurred sturgeon spawning, and with those pulses being blocked by dams there is little spawning. Large scale inflow of pollutants from many sources over the length of the species range may also negatively affect reproduction.

Western Prairie Fringed Orchid

Scientific Name: Plantanthera praeclara

Description: Western prairie fringed orchids grow up to three feet high and can have up to two dozen flowers arranged on its stalk. Its flower are large, white and have fringes on the margins giving them a feathery appearance.

Preferred Habitat: The orchid prefers high quality moist, tall grass prairie. The orchids appear in only two counties in North Dakota, Ransom and Richland. Most of the orchids in North Dakota are located in the Sheyenne National Grasslands in the Southeast corner of the state. North Dakota has the largest population left in the world, with over 2000 orchids.

Life History: The western prairie fringed orchid is a long lived perennial that arises from a fleshy tuber. Vegetative shoots emerge in late May. The orchid flowers in June and July and is pollinated by hawk moths. The plant can display flowers for about 21 days with individual flowers lasting up to 10 days.

Reason for Decline: The conversion of prairie to cropland is the main reason for the orchid's decline. Fire suppression, overgrazing, non-native plants and herbicides have contributed to the decline. Hydrological changes that draw down or contaminate the water table may also adversely affect the orchid.

What property owners with western prairie fringed orchids on their land can do:

Landowners in western Richland or eastern Ransom Counties that have Western prairie fringed orchids on their property are asked to implement the following practices to reduce orchid exposure to herbicides and other pesticides:

Ground Applications:

1. If plants can be covered with plastic (which should be opaque if the weather is sunny), no use buffer is necessary. Plastic that may contain pesticide residues may be disposed of in landfills.

2. If the wind is blowing away from any orchid sites, use the following buffers between sites of application and orchid plants:

*Wind Speed is 3-7 mph, the Buffer is 20 yards

*Wind Speed is 7-10 mph, the Buffer is 10 yards

3. If the wind is blowing toward the orchid sites from the field, a 40 yard buffer is adequate.

Aerial Applications:

1. If plants can be covered with plastic (which should be opaque if the weather is sunny), no buffer is necessary. Plastic that may contain clopyralid residues may be disposed of in landfills.

2. If there is a foliated shelterbelt or other vegetation higher than twice the aircraft spray height between the application site and the orchid site, the buffer size may be reduced by one‑half of the recommendations below.

3. If the wind is blowing away from the orchid sites, use a 100 yard buffer.

4. If the wind is blowing towards the orchid sites:

a. Keep a 2 mile buffer from orchid sites, or

b. Adjust droplet size to BCPC >coarse= (volume median diameter >370 microns)and keep a 250 yard buffer from orchid sites, or

c. Apply by ground application equipment and keep a 40 yard buffer from orchid sites.

Growers affected by these recommendations (i.e., within 2 mile of orchid sites) and who use any pesticides near orchids are requested to observe orchids periodically throughout the growing season and report anything that looks adverse, even if not apparently due to pesticides, to the Fish and Wildlife Service or the North Dakota Department of Agriculture.

All other conditions, precautions, and restrictions on the pesticide labeling including endangered species bulletins must still be followed.

Gray Wolf

Scientific Name: Canis lupus

Description: Most gray wolves are gray, but their coloring can vary from black to white. Gray wolves are the largest members of the dog family, weighing 70-115 pounds.

Preferred Habitat: Wolves are adapted to many different climates and habitats. They live in such diverse places as the deserts of Israel, deciduous forests of Virginia and the frozen artic of Siberia. In North Dakota there is a not a permanent breeding population of wolves, the wolves that occasionally wonder through the state prefer more wooded areas such as the Turtle Mountains, but they can show up anywhere. Wolves are listed as endangered west of Highway 83 in North Dakota, and are not listed east of Highway 83.

Diet: Main food items are large ungulates: white-tailed deer, moose, elk, big horn sheep, but they also eat beaver and hares. They usually focus on old, weak or injured animals. There are no known gray wolf attacks on humans.

Life History: Wolves often establish lifetime mates and in the springtime have four to six pups. The pups are reared in a den and depend on their mother's milk for the first month, and afterwards are fed regurgitated meat brought back from other pack members. Pups are cared for by the entire pack and by late fall will weigh up to 60 pounds. Young adults will travel together for about two years before they disperse, sometimes as far as 500 miles. Wolves usually breed when they reach two to three years of age

Reason for Decline: The spread of European settlers west depleted wild ungulate populations, the preferred prey of wolves. Wolves then began to prey on livestock, and government agencies instituted a bounty program to eradicate gray wolves.

Whooping Crane

Scientific name: Grus americana

Description: Standing nearly five feet tall with a 7.5 foot wingspan, whooping cranes are the tallest birds in North America. Adult whooping cranes are white with a red face and crown and a long pointed bill and black wing tips. Immature whooping cranes are pale brown.

Preferred Habitat: Whooping Cranes breed and nest along shallow lake margins or among rushes and sedges in wetlands. Whooping cranes prefer sites with minimal human disturbance. During their migration through North Dakota, cranes stop on wetlands, river bottoms and agricultural lands. Whooping Cranes winter on estuarine marshes, shallow bays, and tidal salt flats.

Diet: Whooping Cranes commonly feed on crabs, clams, shrimp, snails, frogs, snakes grosshopopers, larval and nymph forms of flies, beetles, water bugs, birds and small mammals. While migrating through North Dakota, waste grains are an important food source.

Life History: Whooping Cranes are monogamous and pair for life. Each year around April, they return to the previous years breeding grounds. They lay two eggs, two days apart in late April or early May. The eggs are incubated for 29-34 days. Whooping cranes fledge (fly) between 78-90 days, but are fed by both parents for the first fall and winter. Usually only one chick survives. They migrate south from mid-September to mid-October, often with sandhill cranes. Whooping cranes become sexually mature between 4-6 years, and live up to 20 years in the wild.

Reason for Decline: Historical reasons for decline include hunting and specimen collection, human disturbance and conversion of nesting habitat to agricultural uses. These disturbances led to the last record of whooping crane breeding in North Dakota in 1915 and a world wide population of just 16 individuals by 1941. The population is now slowly recovering, but still faces challenges. Currently, the main threats to whooping cranes are the possibility of a hurricane or contaminate spill destroying their wintering habitat on the Texas coast. Cranes are also susceptible to power line and fence collision, avian tuberculosis, avian cholera and lead poisoning.

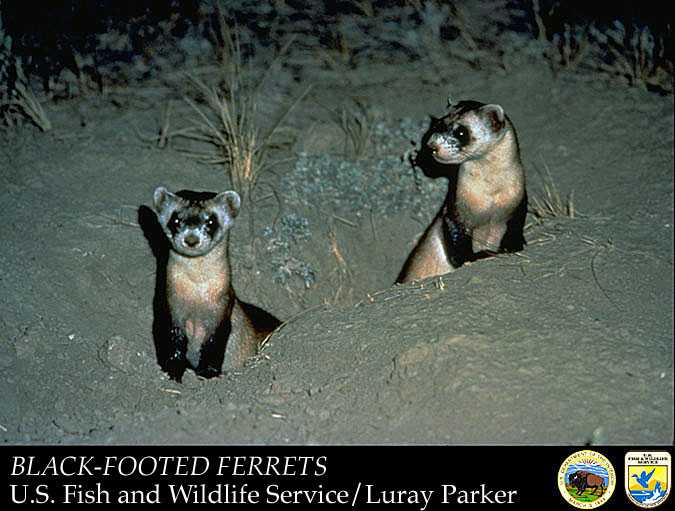

Black Footed Ferret

Scientific name: Mustela nigripes

Description: The only ferret native to North America. They are 18-24 inches long, and have a tan colored body with black feet and legs, a black tip on the tail and a black mask.

Similar species in North Dakota: The related long-tailed weasel is about half of the size of the ferret and does not have the ferret's distinctive black markings. The weasel turns white during the winter months and is common state-wide.

Preferred Habitat: The ferret is associated with mixed and shortgrass prairies, and is always associated with large prairie dog towns. The southwestern part of North Dakota was home to the ferrets historically. Their former range was throughout most of the Great Plains.

Diet: The ferrets' main food is prairie dogs. Ferrets hunt mainly at night so they are hardly ever seen

Life History: In May or June, black footed ferrets produce one to seven kits that weigh only five to nine grams each. The kits are born in burrows created by prairie dogs and stay with the mother until around mid-August. The young become sexually mature around one year of age.

Reason for Decline: The main reason for decline is a loss of habitat. Much of their habitat has been plowed for crops. Black-footed ferrets are obligated to live in prairie dog towns and these towns have been reduced to one percent of their former range due to large-scale poisoning efforts and eradication programs. Prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets are also susceptible to diseases. All these factors contributing to such a great decline that black footed ferrets were once thought to be extinct until 1981 when a dog in Wyoming found one black-footed ferret. This led researchers to a colony of 18 individuals. From those 18 ferrets, the population has risen to about 700 individuals in the wild.